What is Chicano?

What does the term “Chicano” mean? We should begin with a discussion of the roots of the term, not the etymological ones but the historical and social ones. The original use of the word “Chicano” referred to a newly arrived, undocumented Mexican worker. 1 The word “pocho” referred to a Mexican born in the United States or one with a long established residence in the country and therefore more assimilated to American culture and way of life. Thus, the “Chicano” term carried an inferior, negative connotation because it was usually used to describe a worker who had to move from job to job to be able to survive. Chicanos were the low class Mexican-Americans. In the 1960s, the term “Chicano” was consciously assumed and popularized by young Mexican-Americans frustrated with the traditional style of politics in their community that marginalized or even ignored them. It was given a militant political and indigenous connotation as a title of pride and new consciousness. According to Texas artist and curator Santos Martinez, Jr., a Chicano was “a Mexican-American involved in a socio-political struggle to create a relevant, contemporary and revolutionary consciousness as a means of accelerating social change and actualizing an autonomous cultural reality among other Americans of Mexican descent.” 2 To call oneself a Chicano was a blatantly political act and the term served to unify the movement nationally. Today, “Chicano” is a term of identity sometimes assumed by people of Mexican descent born in the United States. To some, it is interchangeable with “Mexican-American” and to others it still carries heavy political connotations. 3

The History of Mexicans in the United States: An Overview

The key to understanding the Chicano experience is to realize that the heritage of people of Mexican ancestry in the United States stretches back hundreds of years to include both European and Native American roots. The Chicano movement had two goals: to seek social justice and equality for Mexicans in the US and to reclaim and educate people of their rich heritage.

Conquest

Since the European invasion and conquest of the New World , persons of Mexican descent have suffered political, social, and economic oppression. It can be said that the Chicano movement has been fomenting since the end of the US-Mexican war in 1848, which resulted in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. As provisions of the treaty, Mexico was forced to hand over the territory that now constitutes the Southwest United States, the Texas-Mexico border was moved from the Nueces River to the Rio Grande, and thousands of Mexicans became US citizens overnight and had their property seized. Since that time, Mexicans in the US have confronted discrimination, racism, and exploitation. 4

http://www.cnn.com/WORLD/americas/9902/15/us.mexico/story.us.mexico.jpg

A Mexican-American Period: 1910-1965

After the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917), millions of Mexicans migrated north to the United States . This immigration produced a strong sense of xenophobic nativism among white Americans. This mass movement of people, one of the largest in history, occurred in the period beginning during World War I, through the expansion of mining and railroads, until the Great Depression of the 1930s. Mexicans comprised a large army of labor for white employers who wanted low-wage workers. Dehumanized and disrespected, Mexican workers were paid barely enough to survive even though they were working long and endless hours in horrible and inhumane conditions. 5 During the Great Depression, from 1929 to the late 1930s, the United States faced an economic disaster of unparalleled dimensions. Unemployment and inflation rates were extremely high and people wanted to find scapegoats to blame. Mexicans, who worked in the harshest conditions in fields where no white man would dare work, were accused of taking jobs away from ‘real' Americans. Mexicans, who had been so desirable as workers in the previous decade, were discharged from their jobs and pressured to return to Mexico by authorities. Between 1929 and 1936, over 600,000 thousand Mexicans, even those born in the United States , were repatriated. 6

By the 1940s, the process of urbanization was transforming the Mexican-American community. Though some entered the skilled labor market, a large majority was kept in poverty through discrimination, racial oppression, and exploitation. 7 During this time period the Pachuco subculture began to emerge. Pachucos were young urban working class people of Mexican descent who adopted linguistic and social behaviors that were neither acceptable to the Mexican or the dominant white community. They wore zoot suits, spoke calo, a slang that mixed English and Spanish, drove hot rod cars, and tattooed their hands and bodies, often mixing Catholic and sexual imagery. Pachucos, like other Mexican-Americans, suffered from poor education, lack of job training and skills, poor housing, segregation, discrimination, and especially, police brutality. In 1943 there occurred the infamous Zoot Suit Riots, during which hordes of police and servicemen invaded the barrios and downtown areas of Los Angeles and stripped and violently beat the zootsuiters in the name of “Americanism.” 8

http://www.dlh.lahora.com.ec/paginas/infantila/entorno35.htm

Chicano Movement Period: 1965-1981

The Chicano political movement grew out of an alliance formed in the 1960s by exploited farmworkers attempting to create unions against the powerful agricultural and ranching businesses in California and Texas , those attempting to repossess lands taken by Americans after 1848, the urban working classes, and the growing student movement. The movement dealt with economic struggles in rural areas and urban issues such as police brutality, civil rights violations, low wages, inadequate housing and social services, gang warfare, drug abuse, limited education opportunities, and lack of political power. The Vietnam War was also a crucial issue.

Labor Struggles

Labor conflict in the large factory-farms where Mexicans were employed under wretched conditions was nothing new. Strikes had been crushed again and again by repressive laws and threats of deportation and violence. The difference in the 1960s was the movement's ability to challenge the ‘green giants' and bring the labor struggle to the attention of the nation and the world. 9 The farmworkers' movement was organized by Cesar Chavez.

Cesar Chavez http://aztlan.net/cesartribute.gif

He began as a voter registration organizer in the 1950s and in 1962 co-founded the National Farm Workers Association with Dolores Huerta, which later became the United Farm Workers of America (UFW). Chavez and Huerta organized movements in California and in the Southwest, with the goals of improving the labor conditions and lives of the migrant farm workers and the recognition of Mexicans as actual human beings worthy of humane treatment. Together, Chavez and Huerta used a nonviolent strategy that included worker strikes, public marches, hunger strikes, and boycotts. 10 During the long struggle, Chavez received help from various sources. He began an alliance with other trade union movements, especially the AFL-CIO, Protestant and Catholic religious organizations, radical student associations, and other civil rights groups. The basic tactic was the huelga, or the strike. Recognizing the limited potential of the strike, Chavez and the UFW came to rely on the boycott, which meant his success would depend on support in urban areas as well as rural ones throughout the country. The first nationwide boycott of any kind against nonunion grapes was extremely successful. Seventeen million people, or 12% of the American adult population, participated and effectively wiped out grower profits. 11

Land Struggles

Reies Lopez Tijerina, an itinerant preacher who had once been a migrant worker, led the movement to reappropriate lands lost by Mexicans after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. He spent years doing research and collecting data on Spanish and Mexican land grants in the Southwest and founded the Alianza Federal de Mercedes, a movement that took on the plight of New Mexico's small farmers left landless as a result of the US-Mexico war. Its goal was to return rightful ownership to Mexican-Americans of the common-use lands seized from Mexicans after the war. Tijerina was not only committed to mobilizing rural Chicanos to take back their lands but also to reinstitute their culture and language to the lands. With the motto “The Land Is Our Inheritance, Justice Is Our Creed,” Tijerina and the Alianza organized a march from Albuquerque to Santa Fe in 1966. This was an important march because, although it was unsuccessful, it affirmed the identity of Chicanos as a new breed, a new race, “La Raza.” It established Chicanos as people of the New World Hispanic culture with many influences from Native American sources. In 1967, Tijerina and twenty other Alianza members raided the courthouse at Tierra Amarilla of the Rio Arriba County and achieved national recognition. 12

Urban Agenda

In the urban centers, Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales was establishing himself as the leader of the Chicano student and youth movement.

Corky Gonzalez http://www.albany.edu/jmmh/vol3/chicano/corky.gif

Demands included better education opportunities for their communities and social reforms dealing with police brutality and the prison system. Gonzalez brought Mexican-American students and youth from across the Southwest together for a first time through a series of conferences, the most important in Denver in 1969. Called the “Crusade for Justice,” Gonzales and his followers stressed the need for students and youth to play a revolutionary role in the movement and forge a new Chicano identity. 13 The new identity would reflect a total rejection of Anglo culture and base itself on symbols of traditional Mexican culture. The resolutions adopted by the conference were put together in a document called El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan. Aztlan, an Aztec term, represented a spiritual return to the Mexican homeland for Chicanos: a homeland that included the Southwest and California. 14

http://www.stoptheinvasion.com/AZTLAN%20MAP.jpg

This represented the beginning of a Chicano-Indian alliance, born from a sense of shared oppression and racism, and was manifested in Chicano art with images of Indian leaders of the past and present. The term “Chicano” became an expression of an assumed militant political and Indian-oriented consciousness. 15

La Raza Unida: The Chicano Party

One of the major outcomes of the 1969 National Chicano Youth Liberation Conference in Dever, Colorado was the call for a creation of an independent local, regional, and national political party for Chicanos. The Democrats and Republicans had been denounced for not responding to the needs of Mexican Americans. The Mexican American Youth Organization and Jose Angel Gutierrez organized a takeover of the school system in Crystal City, Texas. After a successful student strike at the local high school, Gutierrez, a gifted organizer, lost little time in continuing his efforts for more educational equality. With the help of his wife, he created El Partido de la Raza Unida in January 1970 and in subsequent elections, the party was able to elect its candidates to both the school board and the city council, soon gaining control of them. These victories, interpreted as a Chicano takeover, stimulated interest in La Raza Unida party and chapters sprung up all over Texas and began to emerge in Colorado and California. 16 The party's platform proposed reforms in education, economics, the justice system, and immigration policies and advocated women's rights. The proposed reforms were not at all revolutionary. For example, they asked for hiring of minority counselors in high schools with majority Chicano student populations and elimination of standardized test biases toward Anglo-Americans. 17 Economically, La Raza Unida called for the reduction of regressive taxation and distribution of wealth on a more equitable basis. They proposed the creation of civilian police review boards for better protection against police violence and prison reform. 18 Third parties in the United States have historically found it difficult to survive, let alone make any substantive impact on the two-party system. By 1973, although successful on the local level, La Raza Unida proved to be no different. Its failure was in part due to its inability to secure official ballot status in California and to achieve ideological unity. For example, there were conflicts of interest between Californians and Texans. Also, a clear difference was emerging between a more Marxist sector of the party (who wanted to include other races) and a more nationalist, less radical sector. Also La Raza Unida was closely tied to student movements on campuses. So when student movements declined and attention was turned elsewhere, the party lots its most dynamic component. 19

http://www.mexika.org/PNLRU.gif

The Vietnam War

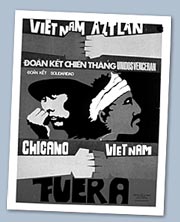

From 1964 to 1972, the United States was involved in military conflict in Vietnam that eventually spread to Cambodia and Laos. The country experienced the greatest antiwar movement in its history. This movement protested the 50,000 deaths, 250,000 wounded, the massacres, and the brutalities on both sides, and the fact that there seemed to be no end in sight. Mexican-Americans, as well other ethnic minority groups, were the earliest opposition against the war because they felt too many of their own were dying in Vietnam in what many considered a white man's war, while their people lived in poverty and racism in the US. As early as 1967, Chicano leaders like Corky Gonzalez and Reies Lopez Tijerina were speaking out against the war. Several Chicano moratoriums were organized, culminating in the National Moratorium in east L.A. where 20,000 to 30,000 people participated. The demonstration was attacked by sheriffs and police and resulted in the death of one man, Ruben Salazar. 20

This poster, created in 1972 by artist Malaquias Montoya, addresses the political struggles discussed above. Not only were Chicanos suffering discrimination, poverty, and police brutality at home, but they were dying in disproportionate numbers in Vietnam. The author is also making an appeal to solidarity between Chicanos and Vietnamese.

http://www.kqed.org/w/snapshots/images/photo_05_01.jpg

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.