|

William Hogarth, A Committee of the House of

Commons ( 75) |

|

| The representation

of blacks in English art most commonly emphasized a role of subservience.

William Hogarth's A Committee of the House of Commons (left)

depicts one black man amongst a crowd of established white men. The

delineation of power is obvious: all of the members of Parliament

are standing or sitting in a liesurely manner while the sole black

man depicted is carrying a heavy burden on his shoulders. |

| There are

two possible interpretations of this scene. One is a commentary on

the pretentiousness of the powerful white man, who allows others to

do his work for him. The other is an endorsement of race and class

stratification: white males deserve their positions of power while

black males deserve only a miserly station. Though Hogarth used his

art to criticize the upper-class (76),

the manner in which the black man is depicted in this work is similar

to those artists who portrayed blacks as inferior. |

|

| Black

inferiority was often represented through animalistic characteristics.

As described in the religious debate,

blacks were not considered human beings by many people, but rather,

as beasts. |

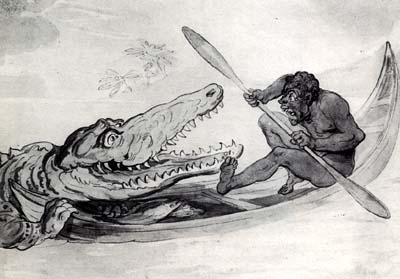

| Rowlandson's

Broad Grins (right) is an excellent example of this mentality.

The facial similarities between the alligator and the black man are

striking. Both have very wide, round eyes. The man has a long nose,

and long, sharp teeth that are visible through his gaping mouth. The

alligator also possesses these features. This sort of depiction helped

justify the argument that blacks were not human, a common argument

in the 18th century. |

|

|

|

Rowlandson, Broad Grins ( 77) |

|

|

|

Hogarth, Four Times of Day- Noon ( 79) |

|

| Another

common belief during the 18th century was that blacks were savage

and dangerous. For example, some women believed that "Africans

needed to live in English society because it was civilized" (78),

which implied that blacks were savages. |

| Artwork

reflected this mentality and acted as a means to keep blacks in bondage.

Hogarth's Four Times of Day-Noon (left) shows a potentially

dangerous scene. The black man is groping the white female in public.

Open sexual advances were considered crude and even dangerous. The

fact that a black man is touching a white woman would be even more

dangerous since it not only defies sexual norms, but it also crosses

the racial divide. Although Hogarth is satirizing the lower-class

in this work, his representation of the black man still reflects common

misconceptions of the 18th century. |

|

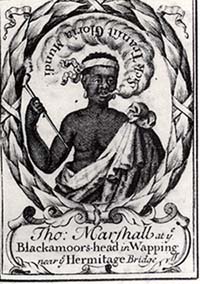

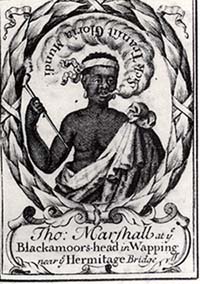

| One other

way blacks were depicted in English art was as the "poster boy"

for the products that they produced. Marshall's Tobacco Tradecard

(right) shows a black man smoking a pipe, and is described in the

caption as a "blackamoor." This has a few implications. |

| The first

is that the black man uses the product that he produced. If a slave

enjoys the fruit of his own labor, then his bondage is justified.

This is a clever strategy on the part of the tobacconist since he

sells a product that was boycotted by abolitionists in England. |

| The other

is that the black man is a Moor. By depicting the black man as such,

the artist creates aversion toward blacks, since Moors were Muslim

and the English were almost entirely Christian. Both of these representations

helped justify using slavery to grow a popular (and profitable crop)

in the British empire. |

|

|

Anonymous, Marshalls Tobacco Tradecard ( 80) |

|